We previously dove deep, then even deeper, into the differences and similarities between barley shochu and malt whisky. I think it’s time we address the other side of the same coin: kourui shochu versus grain whisky.

With the recent announcement by the JSLMA of new standards for Japanese whisky, one thing that’s been highlighted is the requirement that all of the whisky in a given bottle must be fermented, distilled, and matured in Japan. That may seem obvious for a Japanese single malt whisky, but when we talk about Japanese blended whiskies–that is, whiskies made with both malt whisky and grain whisky–things get a bit murkier.Japan’s major whisky makers like Suntory, Nikka, and Kirin have in-house grain whisky operations. That’s a given considering the volume of blended whiskies they sell. It’s no problem for them to conform to the new standards for premium blended whisky brands like Hibiki, Royal, Taketsuru, or Fuji.

But what about the rest of Japan’s whisky makers? Given that–unlike Scotland–Japanese whisky distilleries don’t exchange stocks, thanks to the new standard, anyone without an in-house grain whisky capability is essentially locked out from producing standard-conforming blended Japanese Whisky. They face a tough choice: a) source grain whisky from outside of Japan, rendering them unable to use the “Japanese whisky” designation, or b) create their own in-house grain whisky operations.

I think there’s a third option. What if an established kourui shochu maker decided to enter the grain whisky market, supplying grain whisky to these makers?

Grain Whisky: Malt Whisky’s Industrial Cousin

Grain whisky, as you may have gathered from the name, employs a variety of different grains. Often wheat, corn and rye. These grains are generally mixed with a bit of malted barley for saccharization purposes, yielding wort. The wort is fermented, making what’s called wash, which is then distilled to a very high purity (96% abv) using a column still, otherwise known as a “continuous” still. It’s not impossible to use a pot still to make grain whisky (like you would for malt whisky), but continuous stills are more common.

And you can make a lot of it. Because you can keep on feeding wash into the continuous still even while it’s running, you don’t need to employ batches like you would in a pot still. Thus the name continuous still! That said, the end product is usually less flavorful than malt whisky.

Less flavorful doesn’t necessarily mean worse: in the latter part of the 19th century, pioneers like Andrew Usher realized that mixing malt whisky with grain whisky yielded a less overwhelming Scotch that was more appealing to everyday drinkers. Given the high volumes associated with grain whisky production, this allows makers to “stretch” their malt whisky stocks a lot further. Cue the blended whisky renaissance.

So when we talk about grain whisky, it’s important to highlight that economies of scale are the major driving force. Without grain whisky, the world’s best-selling Scotch brands like Johnnie Walker, Ballantine’s, Chivas Regal, and Dewar’s would simply not be possible.

Japanese grain whisky case study: Chita Distillery

Here in Japan, Suntory’s Chita Distillery is Japan’s largest whisky distillery by volume. The site has a very industrial feel to it, with 30m high steel towers that you may think are part of the ENEOS oil refinery that’s mere meters away.

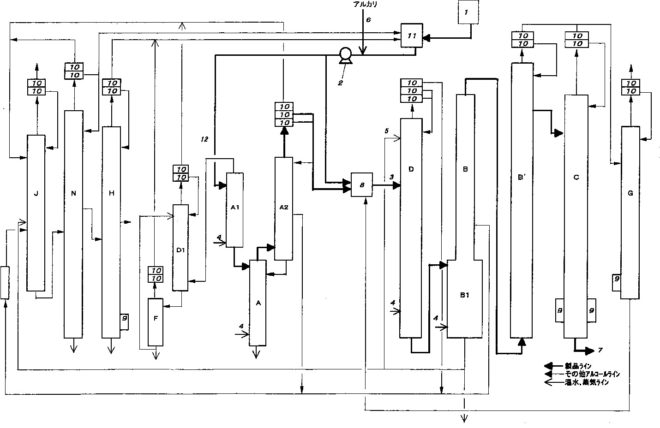

The distillery has two sets of four columns: a wash column, extraction column, rectifier column, and refining column. “Clean type” Chita uses all four columns, “Medium type” Chita uses three, and “Heavy type” Chita uses two. Clean goes into Kakubin White, Medium into Kakubin Yellow, and Heavy into Kakubin Black.

Chita’s location right at the Port of Nagoya allows easy access to the huge container ships full of grain from abroad. In fact, Chita began its life in 1972 as the “SunGrain Chita Distillery,” a 50/50 joint venture between Suntory and the National Federation of Agricultural Co-operative Associations, better known as “Zen-Noh.”

In addition to saving on transport costs of the raw materials, the location helps reduce costs of the final product. Chita is located within easy access of Suntory’s Yamazaki Distillery, Hakushu Distillery, and Ohmi Aging Cellar.

From Suntory’s perspective, these logistical wins are more important than marketing-pamphlet factors you might see with a malt whisky distillery. Things like the local aging environment, purity of the local water supply, and a pristine, picturesque location.

If this isn’t the impression you had of Japanese whisky, you’re not alone. In fact, that’s precisely why Suntory doesn’t allow public tours of Chita: they don’t want people associating this kind of large-scale, industrial operation with whisky.

It didn’t stop them from making this “concept movie” though.

Japanese Whisky is popular, but is it big?

While all of the new Japanese whisky distilleries popping up and ballooning export values are further evidence of the growing popularity of Japanese whisky, the volumes produced by these craft distilleries are still very small. That’s partly because they have focused exclusively on making malt whisky in small batches, where their 1 ton malt batch yields something like… a single 400L barrel of whisky.

400L might still sound like a lot to a regular drinker. But it’s only about 570 bottles, assuming cask strength. That’s 570 bottles for the entire world. Releases of only a few hundred or thousand bottles virtually guarantees that these brands won’t find their way to most liquor store shelves. They will only appeal to a niche audience for the foreseeable future. For comparison purposes, someone like Caol Ila produces about 6.5 million liters per year.

While “make even more malt whisky” is one solution — a solution Chichibu has already chosen — make grain whisky is another.

who will be the next chita?

The capital expenditure required to build a grain distillery is an order of magnitude higher than what’s required to build a malt distillery. The above-mentioned Chita, for example, records fixed assets of 6.5 billion yen (about $59M USD) on their balance sheet. That’s a lot of money, especially since Chita doesn’t sit on the casks they fill.

While I wouldn’t say it’s impossible — a joint venture might happen, who knows — I don’t expect craft whisky makers to come up with tens of millions of dollars to build their own grain distillery any time soon.

But!

What if some company already had most of the infrastructure required to produce grain whisky at scale? What other spirit in Japan has the same kind of volume-based, industrial approach?

The answer is kourui shochu. I think it’s entirely plausible that we see one of Japan’s major kourui shochu makers enter the Japanese grain whisky market. They’ll leave malt whisky to the craft distilleries, supplying them with grain whisky direly needed to increase the reach of their brands.

Kourui Shochu

Ordinarily, when we talk about “shochu” here at nomunication.jp we are referring to what’s called honkaku shochu. Like malt whisky, honkaku shochu has that sort of hand-crafted, local ingredient, lovingly-created image. Single-distilled, grandpappy’s secret recipe and all that.

Kourui shochu, on the other hand, is a drastically more working-class style of shochu. It tends to be distilled to a very high purity — an abv of around 96%. Kourui shochu eventually finds its way into your belly via izakaya staples like the shochu (“naka”) component of Hoppy, the ubiquitous lemon sour, ochawari (shochu and tea), and countless other call drinks. All very affordable, and very suitable to guzzle. It’s the Taro Sixpack shochu.

And it turns out that there are a lot parallels that we can draw between the manufacture of kourui shochu and that of grain whisky.

RAW MATERIALS

Let’s begin at the beginning: the ingredients.

Grain whisky’s ingredients

Grain whisky is made from corn, wheat, rye, Looking to Chita, the main one is corn. In Japan’s case, much of the corn is brought in from the south of France.

Apart from corn, about 20% of the total volume of grain whisky is malted barley. It’s added along the way — malted barley’s enzymes help with saccharization, as otherwise it’s difficult to convert the starches in corn to sugar. Yeast is of course necessary for fermentation.

Kourui shochu’s ingredients

Most kourui shochu starts its life outside of Japan. Specifically, in South America.

That’s because cane juice and molasses are kourui shochu’s main raw ingredients. Both come from sugarcane: molasses is a byproduct of making sugar, and cane juice is the juice that comes out when you press sugarcane. And both have a significant advantage compared to grain: they don’t need to be saccharified. This means you can immediately ferment either of them without having to bother with koji, other enzymes, or malting.

This molasses wash then goes through a continuous distillation… in Brazil. The alcohol produced is still quite unrefined, so when it’s imported into Japan, it’s referred to as “crude alcohol.”

It’s worth noting that crude alcohol isn’t imported to Japan only for making kourui shochu. It also finds its way into non-junmai sake, canned chuhai, cheap whisky (yup), and anti-COVID-19 alcohol disinfectant. You’ll find companies likes Japan Alcohol and Daiichi Alcohol in this sector. In fact, Suntory themselves had to suspend production of some canned chuhai last year because crude alcohol was in high demand worldwide to fight COVID-19. About 80% of Japan’s crude alcohol comes from Brazil.

That’s clearly a departure from what we see with grain whisky, but molasses-based crude alcohol isn’t the only ingredient that goes into kourui shochu. You’ll also find more familiar grains like corn, rice, and wheat, as well as potatoes.

Milling and cooking GRAINS

Moving into production, after inspection, the grains will be pulverized using a hammer and/or roller mill. This is to make their starches more readily accessible.

After milling, the milled grain heads to what’s called a slurry tank, where it’s mixed with warm water of 40-70°C. It’s then moved to the cooker, where the slurry is pressure cooked at about 2 atmospheres from 90-150°C. Depending on the mixture, cooking can be as short as 5 minutes, or as long as 2 hours.

Saccharification of grain

The starches in the grains must be converted to sugar for fermentation to take place.

This is where (pulverized) malted barley is added. The enzymes in malted barley are so powerful–they have a high “diastatic power”–that they can also saccharify the starches in the other grains in the mix. Saccharification takes only about 30 minutes, yielding what’s referred to as wort.

Fermentation

After saccharification, the wort is cooled to 18-30°C. Yeast is then added, and the wort is left to ferment for 3-4 days. The wash ends as 8-11% abv by volume.

Distillation

Here’s where our fun begins, and why I think kourui shochu makers could get involved in grain whisky.

Whether we’re talking about grain whisky or kourui shochu, the wash–be it grain or crude alcohol–is loaded into a continuous still.

But not just any continuous still. The history of modern continuous stills in Japan begins in 1950, when a French company called Les Usines de Melle introduced their “Arospass” continuous still to the country. The first experimental unit started operating at Kyowa Hakko in that same year. By 1951 it was processing 720,000L of wash per day.

the Arospass still

The Arospass still was an easy sell because it had the latest technology: a column specifically dedicated to addressing the azeotrope of fusel oils and alcohol. Without getting too technical, this refers to the how a certain portion of unwanted fusel oils remain in the alcohol regardless of how many times you distill it. Simply adding more plates/columns to the still won’t solve the problem.

Innovation came from water. Fusel oils don’t mix with water, meaning that when you do mix the two, you get an emulsion. The arospass tower adds hot water back to the distillate, dropping the abv down to 10%. This shifts the azeotropic point, enabling the fusel oil to be separated from the water.

The fundamentals of continuous distillation are of course the same whether we’re talking about Arosspass or Coffey or Guillaume or whatever, but all modern continuous stills in Japan are based upon this Arospass setup. Kourui shochu and grain whisky are distilled on the same kind of continuous still.

It didn’t take long for Japan to improve upon the Arospass, and Kotobukiya’s (today’s Suntory) “Super Arospass” still went online in 1955 at their Osaka Factory. Modern Arospass setups have some 10 to 13 different columns, all serving different purposes, allowing distillers to mix and match to get a specific profile for their spirit.

Note that I said “all modern continuous stills in Japan” above. Some companies are deliberately not using Arospass stills for whisky because the alcohol produced by them is too pure. Case in point: Nikka’s Coffey Grain and Coffey Malt are made using the more simplistic Coffey stills. As recently as 2013, Suntory chose Coffey stills when setting up the grain operation at Hakushu.

Takara Shuzo

There are over 60 companies in Japan making kourui shochu. One of the biggest ones is Takara Shuzo, the owner of Blanton’s bourbon.

The company’s East Japan factory in Matsudo, Chiba, bears a striking resemblance to the Chita Distillery. That’s because Takara Shuzo uses a Super Arospass still to make a wide variety of products including “Jun” kourui shochu at this facility. In fact, they already have a license to distill whisky at the factory. Takara Shuzo is a member of the Japan Spirits & Liqueurs Makers Association, too.

Going forward

One might think that even before the new Japanese whisky standards were announced, some kourui shochu maker would have realized they can get enter the Japanese grain whisky market using their existing Arospass still.

But all signs indicate that this actually didn’t happen. The lack of transparency in Japanese whisky meant that anyone could simply import grain whisky from abroad to mix with their own malt (or imported malt). Put simply, there hasn’t been demand for bonafide Japanese grain whisky from second-tier/craft whisky distilleries. Hombo Shuzo’s Mars Whisky is probably Japan’s fourth best-known whisky maker, but for their blended whiskies, even they went outside of Japan.

With transparency being called for, I think the winds are changing for Japanese whisky. We now have an actual standard that requires grain whisky come from within Japan! Since it’s unlikely that the major existing Japanese grain whisky makers have any spare capacity to go around, I suspect we’ll see some new entrants in the very near future. Kourui shochu makers have a huge advantage, infrastructure-wise, that puts them in an excellent position to enter the market.

Hi there! I created and run nomunication.jp. I’ve lived in Tokyo since 2008, and I am a certified Shochu Kikisake-shi/Shochu Sommelier (焼酎唎酒師), Cocktail Professor (カクテル検定1級), and I hold Whisky Kentei Levels 3 and JW (ウイスキー検定3級・JW級). I also sit on the Executive Committees for the Tokyo Whisky & Spirits Competition and Japanese Whisky Day. Click here for more details about me and this site. Kampai!

2 Comments