It will soon be a century since the birth of the first bonafide whisky distillery in Japan. Japan’s whisky has used Scotch as a model. That’s because Masataka Taketsuru, the first chief of the Yamazaki Distillery and founder of Nikka Whisky, studied at distilleries in Scotland. The whisky of Japan remained steadfast during the Pacific War and the tough period immediately following, and it experienced high growth alongside the miracle of the post-war recovery of the Japanese economy. With Scotch as a model, Japanese has secured its place as a standalone genre of whisky, differing from Scotch, American, and Irish, thanks to Japan’s unique culture of craftsmanship and omotenashi.

Japan’s first bonafide malt whisky distillery was born in 1923. The very first drop came out of the stills at the end of the following year, 1924. In just a few years, Japanese whisky will celebrate its centennial. In preparation, let’s take a look back at parts of the journey Japanese whisky has taken over the past century.

Text: Mamoru Tsuchiya, Yoshitaka Nishida

Images: Mamoru Tsuchiya, Hiroshi Shibuya

This article originally appeared in Japanese in Whisky Galore Vol.19 / April 2020.

Who brought the first whisky to Japan?

Who is responsible for bringing the first whisky into Japan? To answer this question, we need to turn back the clock to about 100 years before Japan built its first whisky distillery.

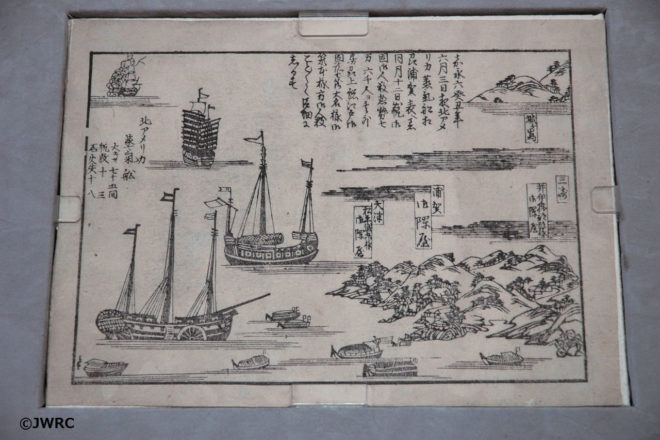

Several historical figures have previously been suggested as the first to bring whisky into Japan: Tokugawa Ieyasu’s diplomatic advisor Miura Anjin (William Adams), Daikokuya Kodayu, a castaway who ended up in Russia, or John Manjiro, active during the Bakumatsu. But there is no hard evidence to back up these claims, and considering the times that each lived in, there are major questions that throw the theories into doubt. So-called “southern barbarian liquor” like beer and wine is said to have been in Japan by the Muromachi period, coming with Christian missionaries and guns to Tanegashima. For whisky however, the prominent explanation backed by historical records is that it was brought on the “Black Ships” that arrived at the end of the Edo period in 1853. Black Ships commanded by Commodore Matthew Perry.

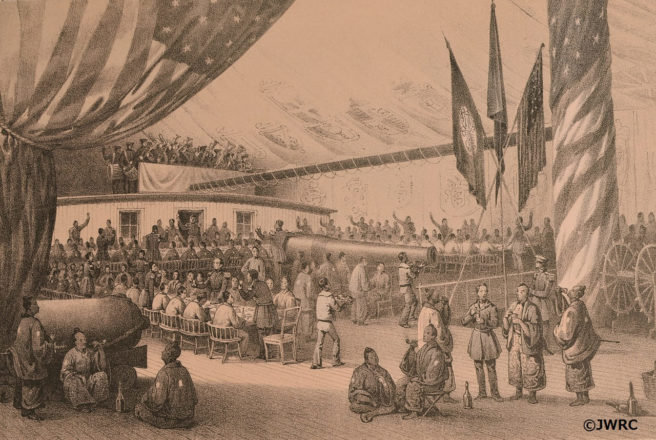

Aiming to open up Japan, Perry’s ships departed the port of Norfolk in November 1852 and arrived in Ryukyu in May 1853. At the time America did not recognize Ryukyu as part of Japan, so they aimed to first sign a treaty with the Kingdom of Ryukyu prior to the doing so with Tokugawa shogunate. Ryukyu records from the time show that the Perry party was warmly welcomed by the Kingdom of Ryukyu, and there is a record of the visitors returning the favor in the form of a party held on the deck of the flagship USS Susquehanna in June 1853. The Ryukyu Kingdom delegacy was treated to all sorts of Western alcohol and delights, including Scotch whisky, American whiskey, wine, port, and punch. The next month, the Perry party arrives in Uraga for negotiations. Invited to the ship was a shogunate delegacy with members such as Tatsunosuke Hori, the shogun’s interpreter, magistrate Saburosuke Nakajima, and Eizaemon Kayama. Whisky was of course served here as well, and the American recordkeeper included a humorous account of their drinking: “Unexpectedly, the Japanese officials enjoyed the John Barleycorn, and disembarked the ship with kimonos stuffed with ham and red faces.”

A year after Japanese people first encountered whisky, the Convention of Kanagawa was signed. At the signing ceremony there were demonstrations of Western technology like steam locomotives and telegraphs. A painting showing the demonstrations still exists today, and in the painting there are also whisky casks. According to records from the American side, those casks were presented to Iesada Tokugawa, 13th shogun of the Tokugawa shogunate. If true, that would mean the Tokugawa clan had a cask of whisky gifted to them in 1854.

Imported Western liquor and imitation whisky

In 1856, Townsend Harris arrives as America’s first Consul General to Japan. That’s followed by the 1858 Treaty of Amity and Commerce, a.k.a. the Harris Treaty, and by the next year, ports at Yokohama, Nagasaki, Niigata, and Hyogo are opened to join the previously opened Hakodate and Shimoda. Yokohama was the first to offer an area for non-Japanese residency, and in the area trade offices and consulates for various countries were constructed. Of those, the “England Bldg No. 1” (today’s Silk Museum) housed the offices of Jardine, Matheson & Company, the world’s first trading company. Partners Jardine and Matheson were both Scotsman, with fellow Scot Thomas Glover dispatched to run the company’s office in Nagasaki in 1859. Other companies like Dent & Co. also setup branches in Japan, and importation of whisky for these foreign residents had begun.

As an aside, at the current Yamashita #70, the “Yokohama Hotel”–Japan’s first Western-style hotel–was built in 1860. Not long after, Japan’s first bar was built inside the hotel. Some 150 years later, an event was held in 2010, where 150 bartenders from the Yokohama area gathered to raise their shakers together.

Even so, the people drinking whisky at those sorts of bars were foreigners. The first record of whisky being imported for Japanese consumption is by Yamashita’s J. Curnow & Co., who imported the so-called “Cat Stamp Whisky” in 1871. 1868 also brought the beginning of the Meiji Restoration, and Japan began down the road of Westernization. This in turn led more and more Japanese becoming interested in imported Western culture, turning them onto whisky.

Of course, at the time, genuine whisky was not made in Japan. Instead it was imitation wine and whisky made by apothecaries that rode the wave of popularity of imported culture. The Harris Treaty required low duties on imports of pure alcohol, to which sugar and spices were added to approximate the flavors and aromas of whisky. The imitations were made by druggists of the day like Tokyo’s Denbe Kamiya and Osaka’s Konishi Gisuke Company.

It was one of those big pharmacists of the day, the Konishi Gisuke Company–located in Osaka’s Doshomachi pharmacy district, where it still stands today–that a 13-year-old Shinjiro Torii joined as an apprentice. Shinjiro soon struck out on his own, founding Torii Shoten at age 20, in 1899. Finding success in imitation wine and liquor, the company changed its name to Kotobukiya Yoshuten in 1906. The next year was the release of their first big hit product, “Akadama Port Wine.”

Building further on this success, the company released “Hermes Whisky.” This compounded whisky matched Japanese tastes, and was successful as well. Even so, at the time, it was this same Shinjiro Torii that painfully realized the need for a genuine whisky made in Japan.

Japanese whisky’s first steps

Momentum to create Japan’s first genuine whisky began picking up from the end of the Meiji period to the beginning of the Taisho era. In 1899 the unequal treaties were lifted, raising import duties on pure alcohol. 1901 also saw an expansion of the liquor tax, preventing the affordable imports of this pure alcohol for imitations. Domestic makers rose to the occasion, with the big-name makers like Tokyo’s Kamiya Shuzo and Osaka’s Settsu Shuzo being coined in the phrase “Kamiya in the East, Settsu in the West.” Settsu Shuzo was a new venture by Kihei Abe, a man who had roots in Yasu, Shiga prefecture but whose family found success in Senba, Osaka’s textile industry. In 1907 Settsu Shuzo’s popularity exploded with the release of synthetic sake and shochu, and in 1911 they dove into imitation whisky with a sweet potato-based whisky. One of the biggest contributors to the company’s success in pure alcohol is Kiichiro Iwai, who would later go on to build the Isawa Distillery for Hombo Shuzo. Iwai was born into a sake making family, and had experience in a factory of the Imperial Army, researching how to make the alcohol of a purity necessary for the manufacture of gunpowder. He is responsible for the creation of the Iwai Continuous Still, the most advanced of its time.

Settsu Shuzo sold pure alcohol to pharmacies and took on contract manufacturing for a variety of products. Shinjiro Torii contracted with Settsu to manufacture his company’s own “Akadama Port Wine” and “Hermes Whisky.” It was in 1916 that a man named Masataka Taketsuru joined Settsu Shuzo as a technician. Masataka came from a branch of the Taketsuru family that had for generations run a sake brewery in Hiroshima prefecture’s Takehara. He was the third son of the family and attended Osaka Engineering High School (today’s Osaka University), where he graduated from the Fermentation department. Iwai was a graduate from the first class of the same program, and it was thanks to Iwai’s pull that Masataka was hired at Settsu Shuzo.

Given that Masataka was put in charge of the mixing of the imitation whiskies at Settsu Shuzo in those days, it’s certain that he mixed “Akadama Port Wine” and “Hermes Whisky” based on Torii’s instructions. They were one of the company’s most important customers. Eventually Kihei Abe made the decision to create authentic whisky. Masataka was hand-picked by Abe to go and learn the ropes of making authentic whisky in Scotland, who was protective about their techniques. Part of the reason for Abe’s choosing Masataka to go to Scotland was the fact that Masataka was a promising young technician. He thought Masataka could marry his daughter Maki, and eventually take over the reins at Settsu.

Off to the land of whisky

Masataka left Kobe harbor in July 1918, and after studying winemaking in San Francisco prior to a harrowing trip across the Atlantic, he finally arrived in Liverpool in December of that year. At the beginning of 1919, while auditing courses at Glasgow’s Royal College of Engineering and Technology and Strathclyde Engineering University, he searched for chances to learn whisky-making. On one of those days, he was invited to visit the home of a girl he met at the university, located in a town called Kirkintilloch, about 20 minutes outside of Glasgow by train. There he was introduced to her quiet older sister, Jessie Roberta Cowan. She would eventually become Masataka’s spouse, the famed Rita. The Cowan family had lost the father, a doctor, and at the family’s prompting Masataka took a room on the large property. It was also around this time that Masataka began the translation of J.A. Nettleton’s The Manufacture of Whisky and Plain Spirit, a book recommended to him by his mentor Professor Williams. Though it took a while, he was finally starting to get more serious about studying whisky in Scotland.

In April 1919, Masataka traveled from Glasgow to Elgin to meet Nettleton himself. While Nettleton would not have him, he was able to land a week-long unpaid internship at the Longmorn Distillery. In June of the same year, he likewise spent 3 weeks in Bo’ness learning how to operate a continuous still at a grain whisky distillery, and also time in France and Germany learning about winemaking. Towards the end of that year, he was also able to land an internship at Campbeltown’s Hazelburn Distillery, which was in those days operated by the owner of White Horse, Mackie & Co (Distillers).

With his departure to Campbeltown, Masataka and Rita overcame significant opposition from their families and signed their marriage certificate in the Glasgow registry office. That was in January 1920. In Campbeltown, the new couple began their life together, and in February, Masataka began his three month internship at the Hazelburn Distillery. His records of the internship, the “Internship Report #1 and #2,” nicknamed the “Taketsuru Notebooks,” would later go on to form the cornerstone of Japanese whisky.

Chance meeting of the fathers of whisky

Along with Abe, who visited Scotland immediately upon hearing of the marriage of Masataka and Rita, the three returned to Japan in November 1920. Masataka of course dreamed of building a distillery in Japan as soon as possible, but that dream would have to be put on hold. 1918 was the conclusion of WW1, and the wartime economy collapsed to recession. Making a big investment into whisky-making was impossible for Settsu Shuzo.

As a result, Masataka left Settsu Shuzo in 1922, and had some off-time with Rita in Osaka’s Tezukayama. Masataka taught chemistry at a Momoyama Junior High School, and Rita taught English and piano to rich children nearby. After about a year of that life went by, Masataka and Rita were visited by the boss of Kotobukiya, Shinjiro Torii. Separate from Abe at Settsu Shuzo, Shinjiro was also moving towards making genuine whisky in Japan. Through the London branch of Mitsui Bussan, he planned to bring a technician in from Scotland. But he also heard a name he was already familiar with: Masataka. Shinjiro had come to scout Masataka.

In 1923, at age 28, Masataka joined Kotobukiya, and the plans for building Japan’s first authentic whisky distillery were finally laid out. Masataka’s contract was for 10 years. Shinjiro offered a yearly salary of 4000 yen, a salary that matched Japan’s cabinet ministers of the day.

Japan’s first whisky distillery launches

Where should Japan’s first actual whisky distillery be built? Masataka proposed the lands of the north as being ideal, but Shinjiro was adamant that it be located near where the whisky would be consumed. After surveying locations nationwide, they ended up choosing Yamazaki, located on the border of Kyoto and Osaka. With the Tennozan Mountain Range rising in the north, the site has water famously used by Sen no Rikyu for tea. Additionally, three rivers converge nearby: the Uji River, Katsura River, and the Kizu River, meaning there’s a thick fog year-round. This presence of such a famous water source and the humid climate were ideal for making whisky.

Construction of the Yamazaki Distillery began in 1923, and was completed the following year. A cask of the first whisky that was distilled at the end of that year remains on display today.

The Yamazaki Distillery of those days, under Masataka’s direction, had two genuine pot stills that looked like those at the Longmorn Distillery. Peat imported from the UK was used along with Japan-grown barley that was malted on-site at the distillery. It was all done following Scotch traditions to a tee. Not many people in those days knew how many years it actually took to mature whisky. Huge quantities of barley were being taken into the distillery each day, but no whisky was coming out. Locals that saw this happening began to murmur that a monster named “usuke” lived inside.

After some period of trial-and-error, the first genuine Japanese whisky, nicknamed “Shirofuda,” was released. The extreme catch copy with its release read:

Wake up, people! The days of blind acceptance of importing culture are over. For drinkers. Made in our country. The ultimate in spirits. Suntory Whisky!

Shirofuda’s price, in today’s terms, was about 10,000 – 20,000 yen per bottle. With a smoky flavor that Japanese people weren’t used to, it was an utter failure.

Dreams of making whisky in the north

With the failure of Japan’s first whisky, Shirofuda, Kotobukiya began having to sell off their well-performing businesses, like “Sumoka” toothpaste. And as a successor to Yamazaki Distillery chief Masataka, Shinjiro’s son Kichitaro was reaching maturity. Masataka and Rita had taught him during their Tezukayama days and had, according to Kichitaro, loved him as their own son. After becoming the vice president of the company, Kichitaro passed early, at age 31. With no place at Kotobukiya, Masataka’s last job was restarting a beer factory in Yokohama. His 10 year contract up, in March of 1934, he left the company and decided to pursue his own dreams.

In July of that same year, Masataka founded the Dai Nippon Kaju Company, intending to build a distillery. In Osaka, he found investors such as Tamesaburo Yamamoto and Matashiro Shibakawa of the Shibakawa Building. In total, he collected about 100,000 yen, which is said to be about 1/20th the construction budget available for the Yamazaki Distillery. Of this, Masataka contributed 20,000 yen of his own money.

Looking to finally realize his dream of making whisky in the north, Masataka chose Hokkaido’s Yoichi as the location for the distillery. Conditions were perfect for making whisky: a cool, moist climate, nearby barley fields and peat marshes, and even mizunara forests for making casks. Masataka’s reason for choosing “Dai Nippon Kaju” (“Great Japan Fruit Juice”) as the company name is that, in order to fund the malt whisky manufacture later on, the company began selling apple juice with Yoichi’s plentiful supply of apples. Exactly as planned, Yoichi Distillery began whisky production in 1936, two years after it was built. In 1940, their first ever whisky was released as “Nikka Whisky.”

War, then post-war recovery and to the age of whisky

At around the same time, in 1937, Kotobukiya released “Kakubin,” (12 year). This is when Japanese whisky began to finally find an audience amongst the drinkers of Japan.

But in 1941 the Pacific War began. Since both Yamazaki Distillery and Yoichi Distillery were designated as factories supplying the army, they received preferential treatment for supplies of raw materials, and were able to continue making whisky throughout the war. By the end of the war, in August 1945, Yoichi Distillery was unscatched by bombing and sitting on stock of the whisky they made during the war. Kotobukiya lost both their Osaka headquarters and Osaka factory to bombs, but the Yamazaki Distillery and its stocks were left unharmed.

Eight months after the end of the war, in 1946, Kotobukiya released “Torys Whisky,” using that whisky from Yamazaki. In 1950, they released “Old.” Nikka Whisky, the name by which the company was known from 1952, also had releases like “Special Blend Whisky” in the same year. The recovery of whisky slightly preceded the post-war recovery of the Japanese economy.

Then, in 1949, the liquor tax law was revised again, introducing a grading system with Grades 1 to 3 (a “Special” Grade was added in 1953), dictating the level of genuine whisky that needed to be be mixed into a given bottle. 1955 saw the construction of the Karuizawa Distillery by Daikoku Wine (today’s Mercian). There were also other new entrants to the market, such as in 1973 when Kirin-Seagram built the Fuji Gotemba Distillery. This led to an unprecedented whisky boom in the 1970s and 80s. That boom reached its peak in 1983, when yearly shipments of Suntory’s “Old” hit 12.4 million cases. With one case containing 12 bottles, that was an unprecedented 148.8 million bottles per year, a single-brand record that remains unbroken today.

Nowadays, Japanese whisky is arising from its low point, like a phoenix rising from the ashes. Japanese whisky, now nearly 100 years old thanks to the efforts of great forefathers like Shinjiro Torii and Masataka Taketsuru and those that supported them, is poised to leap into a new era.

Mamoru Tsuchiya is Japan’s foremost whisky critic. He is the Representative Director of the Japan Whisky Research Centre, and was named one of the “World’s Best Five Whisky Writers” by Highland Distillers in 1998. He served as the whisky historian for NHK’s Massan and he has published several books such as The Complete Guide to Single Malt Whisky, Taketsuru’s Life and Whisky, and The Literacy of Whisky. He is the editor of the bimonthly Whisky Galore, Japan’s only print whisky magazine.

One Comment