2018 marks a century since the founder of Nikka Whisky, Masataka Taketsuru, set out on a journey that would alter the history of Japanese whisky. Based primarily on his serialized autobiography originally published in Nikkei in 1968, in Part Three of this series we look at his successes and challenges encountered during his time in Scotland. Read Part One and Part Two for the backstory.

Learning in Rothes

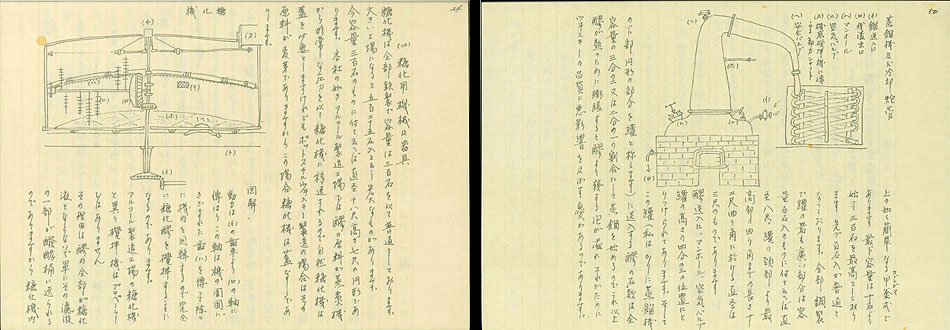

Speyside remains a mecca of Scotch today. Back in Taketsuru’s day, Highland malt distilleries were especially concentrated in the small towns of Rothes, Dufftown, and Knockando. Most of his time was spent at the Longmorn-Glenlivet Distillery in Rothes, but he also saw Glen Grant, Glen Spey, and Glenrothes.Everything that he learned, saw, and felt, he would record that same day in his notebook, using both words and illustrations. “That notebook was really helpful after I went back to Japan and we started making actual whisky at Kyoto’s Yamazaki Distillery,” he recalls. That notebook became to be called the “Taketsuru Note,” and is probably the most important piece of history there is for Japanese whisky. The original is on display at the Yoichi Distillery, and there have been some modern reproductions made as well.

Life in Rothes for Taketsuru was quiet, as most of the villagers’ lives revolved around church and passing on whisky-making techniques from generation to generation. Days in winters were short, and summers were long. One of their few pleasures was meeting at the local hotel bar and playing green bowling outside.

Taketsuru would travel by train between Rothes and the Longmorn-Glenlivet Distillery daily. While its history goes back to 1824, during Taketsuru’s time there, they had only one wash still, one spirit still, and around ten employees. He quotes the head distiller at the time, Captain Bill Smith Grant: “whisky making, like golf, can’t be learned by just reading a book or seeing it done. Your body needs to learn it.”

And that’s exactly what he was doing — everything from shoveling barley while it’s still being malted and smoked with peat, to cleaning the inside of the stills. He was determined to learn as much as possible before heading back to Japan. “In fact, it was because I had this experience of cleaning the kettles that we were later able to make the first pot stills in Japan once we made the first factory at Yamazaki,” he recalls. Under Mr. Grant, he also learned techniques like knocking on the still to listen to how it echoes, revealing how the distillation is proceeding.

Glenlivet is known for quite peaty malts, which while young, are actually pretty rank. But as the years and months go by in the cask, that foulness turns into amazing aromas. Taketsuru was determined to take those aromas back to Japan with him. This determination would later end up putting a rift between Taketsuru and his future employer/Suntory founder, Shinjiro Torii.

Getting Homesick, Staying the course

Around the 7th or 8th month, Taketsuru began to get homesick. In early 20th century Scotland, there were no other Japanese people, no Japanese food, and no rice. Even the newspapers mentioned nothing of Japan — simply that the country was one of the participants in the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. The only thing that reminded Taketsuru of home was the smell of boiled potatoes. He writes about a recurring dream he had, where he spent 50 days at sea return to Japan, then immediately sent back to Scotland to finish his studies by his mother.

The more Taketsuru learned about whisky making, the more he learned how complicated it really is, requiring specific topography, climate, and water. He began to understand how the locals thought that the land itself made the whisky. “I felt like it was a mystery, how whisky made under certain natural conditions would go and mature. Even whisky made at the same time with the same method would end up different after maturation, and casks at the top of the rack would be different from casks at the bottom. It so delicately influenced by nature that it felt alive,” he writes.

Although it was a mecca of whisky, Rothes was a village at best, with no foreigners besides Taketsuru. This made him into something of a local celebrity, and everyone treated him well. It was one of the few comforts he had. He was often invited to visit distilleries in Knockandu and Duffton, as many of the distilleries’ employees lived in Rothes. He would hear their history and got to sample their secret stashes of 10-year or even 12-year whiskies. Besides his own Longmorn-Glenlivet Distillery, he was well-known enough at the Glenspey and Glenrothes distilleries that they treated him like an employee.

The whisky making season ran from October to April, and it was not made during the warmer summer months. On the other hand, this was prime winemaking season for Italy and France. Taketsuru was at Rothes from November 1918 to May 1920, so during these off months he would head back to Glasgow University to study, then visit places like Bordeaux in France to learn about winemaking as well.

“Looking back, I’m amazed that I was able to keep that up,” he writes. “That must have been because I was young and able to absorb anything, allowing me to stay focused.”

Towards the end of June in 1919, fate would strike Taketsuru once again.

New Encounters

Taketsuru had finished up his first year learning distillation at the Glenlivet Distillery, and was back at Glasgow University attending classes. While not exactly friends, he would exchange greetings with a female student named Ella. Then one day, out of the blue, Ella asked him to join high tea at her home. It turned out that her father, a doctor at the university, was a Japanophile.

Ella’s home was located in Kirkintilloch, near Glasgow. The house was so big that it was used as city council chambers up until 1985. Ella’s family consisted of her two parents, two sisters, and a brother. At the high tea, Taketsuru answered questions about his home in Japan, what brought him to Scotland, and more.

Seated next to her father, one of Ella’s sisters watched Taketsuru with big, beautiful eyes. When Taketsuru was talking about being homesick, she said something inaudible under her breath.

It was the first time she and Taketsuru met. Her name was Rita.

Hi there! I created and run nomunication.jp. I’ve lived in Tokyo since 2008, and I am a certified Shochu Kikisake-shi/Shochu Sommelier (焼酎唎酒師), Cocktail Professor (カクテル検定1級), and I hold Whisky Kentei Levels 3 and JW (ウイスキー検定3級・JW級). I also sit on the Executive Committees for the Tokyo Whisky & Spirits Competition and Japanese Whisky Day. Click here for more details about me and this site. Kampai!

Hi Richard,

Great series! Thoroughly enjoyed it, as I do the rest of your website! On small thing I would like to point out is that Taketsuru actually enjoyed his apprenticeship at Longmorn distillery, rather than Glenlivet. The distillery was known at the time as the Longmorn-Glenlivet distillery, and Taketsuru refers to it in his writings simply as Glenlivet.

Kanpai!

Hi Laurens, thanks for the correction! Glad you enjoyed the series and the site.